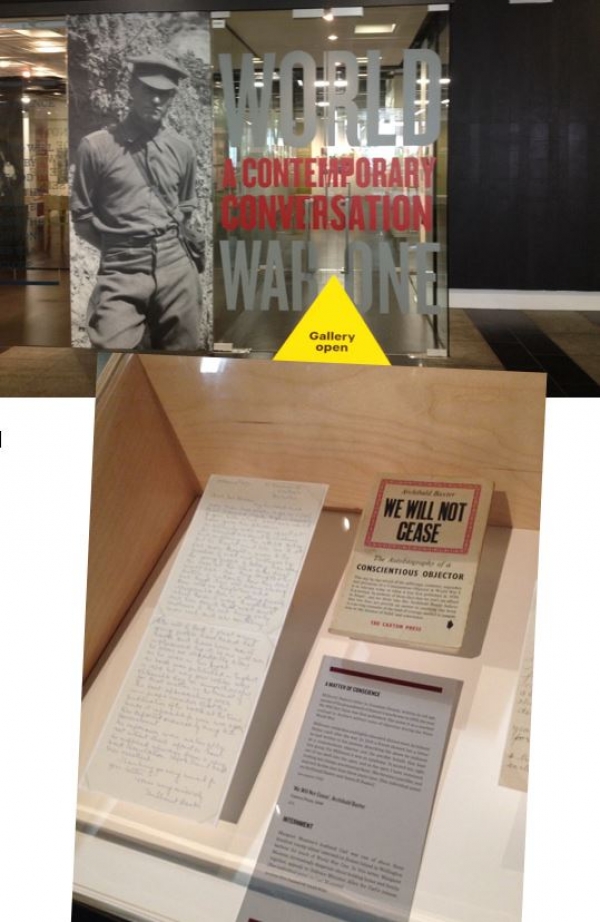

World War One. A Contemporary Conversation

Written by Soldiersandorder NZ-FRIn the National Library of New Zealand, called the Alexander Turnbull Library, in the capital city Wellington, there is an exhibition about WWI. It is called “World War One. A Contemporary Conversation” and is worth a visit if you are on holiday in Wellington.

On display are some information relating to our Shared Histories project. There are two display’s that discuss about the conscientious objector Archibald Baxter. He was sent to France in the First World War and was one of the soldiers given Field Punishment No.1 (known as ‘the crucifixion’).

The exhibition is interesting because it talks about the impact of events on people years later. In one display a letter written by Millicent Baxter to Johnathan Dennis is displayed. She speaks of the growth of dissent towards war in 1939, the year ‘We Will Not Cease’, Baxter’s autobiography about his experiences in the war, was published. She notes it as a marked contrast to Archibald Baxter’s solitary voice of objection during the First World War.

Millicent did not meet Archibald Baxter until after the war. In 1918 a friend showed her a letter he had written to his parents, describing the abuse he endured as a contentious objector and the pacifist beliefs that kept him going. For Millicent it was an epiphany: ‘It moved me, right out of my shell into the open; and in the open I have remained, looking into things, questioning them.’ She became a pacifist, and married Archibald Baxter less than three years later.

Another display in the exhibition discusses how Archibald Baxter’s son, the poet James K. Baxter, was affected by his father’s stance as a conscientious objector. As a child he was often harassed because of who his father was. The young James, persecuted, spent much of his time on his own. But his father’s influence proved to be profound and enduring. At sixteen year old, James K. Baxter was writing poetry about dead soldiers to symbolise his own suffering and that of all of humanity. He eventually came to recognise that what he called the “yoke” of his father’s convictions was actually the bond - the “one aim” – that defined them both.

In his poem “To My Father” James K. Baxter makes reference in one of the verses to his father’s pacifist beliefs.

“We have one aim: to set men free

From fear and custom and the incessant war

Of self with self and city against city,

So they may know the peace that they were born for

And find the earth sufficient, who instead

For fruit give scorpions and stones for bread.”

Latest from Soldiersandorder NZ-FR

- Shared Histories exhibition posters in Wellington

- Prime Minister John Key with Baradene College Students and Shared Histories exhibition.

- Shared Histories exhibition Opening in Wellington. Baradene College students Olivia Mendonca and Genevieve Bowler with the Governor-General of New Zealand, Sir Jerry Mateparae.

- Our project makes it to Elizabeth II Pukeahu Education Centre [Wellington] launch - wow

- Project becomes an e-book at Auckland Libraries!